Georgia Rural Telegraph Museum

by Ken Musson

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", October 1996, page 19

LESLIE, Ga. — From the days of communication instruments which were little

more than tin cans linked by a taut string to today’s telephones using Telstar

space satellites, the history of telephones is displayed in a recently-opened

museum in a tiny south Georgia town.

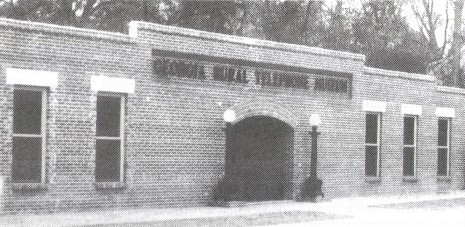

Housed in a former cotton warehouse built in 1911 across State Road 195 from

the Citizen’s Telephone Company building is Tommy C. Smith’s Georgia Rural

Telephone Museum which officially opened Oct. 5, 1995.

In its 18,000 square feet space are displayed about 2,000 telephones and

other communications equipment dating back to the 1800s when Alexander Graham

Bell and others began developing such devices.

The French, led by Charles Bourseul, began talking about midway through the

1800s about using some sort of diaphragm to carry vibrations between one point

and another through electrical circuits. Then a German physicist, Johann Philip

Reis, managed to build an instrument which could transmit musical sounds but he

was unable to reproduce speech. That feat was left to American inventor Bell who

in 1877 produced the first telephone which could transmit or receive speech.

Smith’s museum is the product of his fascination with those developments as

well as the rest of telephone history. He has owned and operated the Citizens

Telephone Company since 1946 when he bought it using a GI Loan for $4,000. Just

out of the Army after World War II, Smith was ready to settle down at a job

doing something other than the farming this part of Georgia traditionally has

thrived on.

The company’s headquarters is in this town of 300 residents about midway

between Americus and Cordele on U.S. Highway 280.

As far as Smith can determine, his is the largest collection of antique

telephones displayed in the world. He was proud to offer that bit of news to

those gathered for a Christmas dinner shortly after work began four years ago on

the museum. His own collection of communication equipment is an integral part of

what is displayed. Other collectors and some telephone companies have provided

the rest of the 2,000 items displayed or scheduled to be displayed. Some are

one-of-a-kind articles.

Mrs. Alice Harvard Street, the only guide who also serves as a consultant in

the area of antiques, enthusiastically describes for the visitors such equipment

as an 1877 commercial telephone, one of only two known to exist, or a solar

battery display of the 1950’s.

Mrs. Alice Street, leading a tour of the Georgia Rural Telephone Museum

exhibition, tells Aline Musson, left, and other visitors to the Leslie, Georgia,

facility

about some of the early communications equipment on display. (Photo by

Ken Musson)

Among the 1800’s instruments are a single-transmitter phone and liquid

transmitter, acid conductor models. She points to several versions of the

hand-cranked bell phones known as the “Bell Box” that were invented by

Thomas Watson, inventor Bell’s closest aide.

There are vanity phones and a half-dozen free-standing 6-foot tandem phones

once used in hotel lobbies and hospitals. Around a corner are the “coffin”

phones of yesteryear which featured wooden boxes and were a fixture on many

walls of homes in the early 1900s.

Visitors also see early Bell tap phones, transmitter phones, three-box

phones, candlestick/desk set phones. Fascinating for many are the first acoustic

phones. These made possible the first long-distance service. They carried the

voice all of two miles.

Particular prizes are the “whisper phone” and “hush-a-phone,” both

rare relics that in the 1800’s offered the telephone user privacy with its

large funnel-shaped mouth-piece that, when pushed snugly against the users’

cheeks, made conversations inaudible to those near by. Otherwise, the low

quality of the sounds transmitted and received made most telephone users of

those days speak in a loud voice, easily heard by anyone within the room —

even a large room.

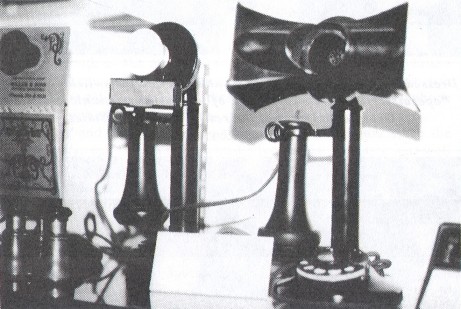

One of the early “privacy” telephones on display at the museum has

wing-like attachments to the speaker portion to reduce the chances

that nearby

people will overhear the conversations. (Photo by Ken Musson)

Early telephone connections were made manually, by operators working at

switchboards in central switching offices. As more and more people began using

telephones, manual switching proved too slow and labor intensive. Thus, pioneer

telephone developers began making mechanical and electronic devices that did the

switching automatically. Today’s telephones use an electronic device to send

either current impulses (as was common with phones using circular dials) or a

series of audible tones (as is common in push-button phones) corresponding to

the number being called. Electronic equipment at a central switching station

automatically translates the signal and routes the call to the receiving party.

At Smith’s museum is a one-of-its-kind 50-line switchboard from 1880 as

well as early one-person switchboards which were usually operated out of the

home of the telephone operator.

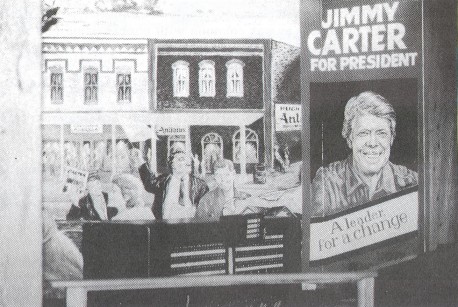

A special display has been set up by Smith and his museum staff to show the

switchboard used by Jimmy Carter in 1976 as he carried out his successful

campaign from nearby Plains to become the nation’s president.

Carter, a featured speaker at the museum’s opening ceremonies, is numbered

by Smith as one of his many friends. Carter told the first-day audience of his

days at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and his yearning to be closer

to Rosalyn Smith (no relation to Tommy Smith of the museum) who was back in

Plains. The future president kept in touch with the woman who would become his

wife through the telephone, linked through Smith’s Citizen’s Telephone

system which also serves Plains.

Carter and those who have toured Smith’s museum since the opening also can

see a wall-mounted silver-dollar pay station as well as pay phones with slots

for each coin denomination. Museum guide Street offers a demonstration of how

the coins dropped into the specified slot provided sounds the switchboard

operators could identify as signals that the proper coin was deposited.

Also on hand for museum visitors to see are examples of the first phone

booths as well as an 1882 headset used by a mannequin depicting a switchboard

operator.

Among the telephone-related items winning prominent display are a wide

selection of glass insulators which once protected telephone lines.

The display also includes a 1930’s telephone truck, seven antique clocks,

an old organ and even a section with nautical antiques which were collected by

Smith who also is a licensed sea captain.

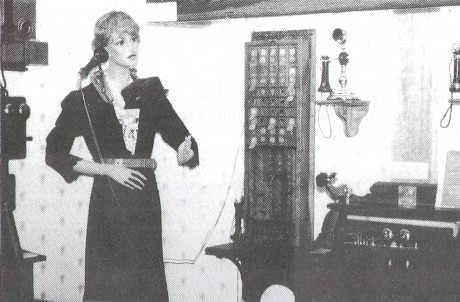

Dressed in period clothing, this mannequin and the switchboard she

"operates" recalls the early days of telephone communications in

Georgia and most of the rest of the United States.

(Photo by Ken Musson)

An early switchboard, complete with stop-watch (at upper left) to time

the calls, is shown at the Rural Telephone Museum with an

accompanying mannequin. (Photo by Ken Musson)

In addition, there is a section dealing with Indian relics and artifacts.

Townspeople made and donated some period clothing adorning mannequins used in

the museum displays and a local hunter provided the deer, a product of a

taxidermist’s skill, which is part of the Indian display.

Background murals have been painted by Georgia artists and depict the way

Leslie looked in the past and still looks today.

Former President Jimmy Carter used equipment in this display at his Plains,

Georgia,

campaign headquarters while seeking office as governor of the state and

later when running his successful campaign to the presidency. (Photo by Ken

Musson)

Smith bought the telephone company from the Stanford family which had

developed it.

“Then, (in 1946) there were only 99 telephones in the exchange and half of

those didn’t work,” Smith told the opening day crowd.

Most were the old hand-cranked versions, he recalled. Today, he has branches

in Plains, Byronville, Lake Blackshear and Vienna, as well as the headquarters.

Showcases housing the old equipment came from an old business in

Jacksonville, Fla. The museum’s interior wood paneling features native cedar

and pine, while the original cypress uprights lend a rural atmosphere to the

remodeled and modern-looking building.

His chief electrician, Howard Stanford, is the grandson of the original owner

of the telephone company. After doing some farming in the family’s

agricultural interests, Stanford joined “Mr. Tommy” and works between the

five telephone offices and the museum building, as the need arises. His father,

Howard Stanford Sr., fashioned and installed the inside paneling in the museum

and also does woodworking chores in Smith’s telephone offices.

Of her husband’s work on the museum woodwork, Betty Stanford says, “I’m

so proud of him I could bust my buttons.”

“This is a family town,” commented the younger Stanford’s mother during

a break from her work at the nearby hardware store.

“Nearly everyone is related to someone here,” she added with a smile.

The hardware store, one of the few businesses in Leslie, is owned by William

“Bill” Derisa, but was originally owned by Mrs. Stanford’s brother.

She recalled that when her husband’s father moved into Leslie in the early

1940’s, the telephone company was housed upstairs above the bank. The family

moved into the upstairs area and operated the company from their living

quarters. The elder Mrs. Stanford was the town’s sole long distance operator

in those days.

So she could serve in that role day and night, she had her husband put wheels

on the cabinet housing her switchboard. That allowed her to roll it up next to

her bed when she retired for the day. It was then easily handy to her to handle

night-time callers.

Leslie is like many small southern towns, explained Mrs. Stanford, who has

been a life-long resident. There isn’t much activity going on there.

Incorporated in 1884, Leslie has had busier times. The economy has always been

steeped in agriculture and resulting cotton and peanut operations. A focal point

of the thriving downtown area of the past was the Seaboard Railroad’s

passenger depot. The depot’s gone, and the biggest industrial operation is the

Green Beans of Georgia vegetable processing plant, situated just west of town

along U.S. Highway 280.

But the economy of the area is still strong. There’s a bank in the downtown

area as well as a post office, a doctor’s office, a couple of service

stations. Two antique stores are ready to serve those who come to town, but they

are opened by appointment only. There’s the hardware store, the old pharmacy,

a grocery store, the telephone company and now, the museum.

Some unused buildings show there were other businesses operating here in

recent years and many of the town-folks say they hope the museum will spark

interest in the opening of some kind of restaurant and perhaps a motel. As it

is, the closest hotel and motels are at Americus or Cordele.

Most people in town, after taking a cautious wait-and-see attitude about

Smith’s plans for the museum, see it as a possible asset for Leslie. Folks

here, as in many small towns, like the rural tone. None of the business people

expresses a desire to see a lot of growth, but a little bit of activity would be

fine.

Hardware owner Derisa also is a member of the Town Council and is mayor

pro-tem.

He calls the museum a good thing for the town and hopes it will draw not only

a lot of visitors but also a few who decide to open the restaurants or motels

neighbors want.

One operator of a service station was fearful of the museum’s effect when

the facility was opened. The highway carrying travelers past the service station

was closed on the museum’s opening day to protect the dignitaries expected to

gather. His station did no business that day.

But on a day soon after the opening, the museum drew a busload of tourists

and the bus driver chose to refuel at that station. The earlier loss was more

than recouped.

There is a beginning of an influx of new young residents in Leslie as they

buy homes in the somewhat rural setting and commute to work in such nearby

cities as Americus, Cordele or Macon, some even to Atlanta. That, says Mrs.

Stanford, is adding “some new blood”.

As for Smith, he’s just sitting back waiting to see how much interest

people will have in telephone antiques.

The non-profit museum operation’s effect on the local tax base is

uncertain. Asked to comment on the use of the building housing the museum for

some of the telephone company business, Smith says simply, “We’re a

non-profit operation.”

None-the-less, there is some cross use of the facility by the telephone

company’s 38 employees.

There’s some talk about adding a gift and souvenir counter to the museum

and there will probably be some more exhibits, but for the time being, Smith is

content with having the attraction up and running.

Among Smith’s early problems was a batch of pamphlets promoting the museum.

Unfortunately, the map showing potential visitors how to get to the museum was

inaccurate and left the attraction difficult to find.

As for the future of the museum, there is more than a little hope that one of

Smith’s three daughters and two stepsons will take up the project if Smith

decides it is time to retire. Already, one daughter and one stepson have worked

for the telephone company.

Difficult to find as it is, by December of its opening year, the museum had

more than 750 visitors who had signed its register. Many described themselves as

workers in the telephone industry or as retired telephone company employees.

Most of those signing the book were from the cities and towns nearby, but a

substantial number came from other states, such as Florida, and even from as far

away as France where the idea of telephones seemed to germinate.

Ken Musson of Bradenton, Florida, is a free-lance travel writer. We are

grateful for his contribution to this month’s magazine. Leslie, Georgia are in

my travel plans. How about yours?

|